For Noni Olaniyan

Her birth name was Andrea and mine was Lynn. Our grandparents and great-grandparents were the by-product of middle passages, migrations, the Jazz era, and probably that bizarre American curio known as miscegenation. Our ever-striving Black parents had great respect for each other and they wanted their children to know each other. Andrea and I were born in the same year, 1957, she in January, me, in August. We knew each other alright.

We met as infants in our mother's arms but I also have real memory of Andrea, or "Bunnie," as she was lovingly called by her family, when we were 11, or was it 12? We were just two quiet Black girls at some holiday gathering. I don’t remember saying much to her then. We seemed dutiful in that Black southern girl way, reflecting the deep love our parents had for us, and for our futures.

We saw each other many times while growing up in different southern cities. My oldest brother eventually made it through his mad crush on "Bunnie" and we would all go our own way out into the scary world. Andrea would leave Atlanta and head for Dartmouth in 1975. I would leave South Carolina, on my way to Talladega, Alabama, that same year. We kept in touch through the telephone game that mothers often play when it comes to their children, long after they leave home, "Where is Andrea now?" "Where did you say Lynn is in school?"

Somewhere around the age of 15 I embraced a more Afro-centric lifestyle. I had older friends who taught me what the state and republic didn’t want me to know, about the beauty and power of 360 degrees of Blackness. Bam! I was hooked. I had two badass, revolutionary, fist-pumping uncles, living out in Los Angeles, who kept me fed on correct Black history, in XL double doses. The day came when I could not resist replacing my white blouses with new wildly colored, dashiki-inspired, culture clothes, all while reading everything from Dr. Frances Cress Welsing, and every chapbook hot off Brother Haki Madhubuti’s Third World Press. Black culture and the arts became my intimate.

I had just moved to Atlanta to attend graduate school at Atlanta University. It was Saturday and there was an African arts festival happening in a nearby park. I could hear the dancing drums all the way over on Avon Avenue where I lived in a tiny shotgun apartment. I pulled a tye-dyed dashiki over my ginormous afro and made my way closer to the sounds of Black life filling up the air. When I arrived the brothers were drumming hard and the buba lapas of the sisters were hiked up and flying in the air like African parachutes. The hands and arms of Black women were moving like glistening swans. Tempeh and tofu sandwiches were saran wrapped tight and stacked on tables out of the sun. Popcorn sprinkled with nutritional yeast, sea salt, and cayenne pepper waited for mouths in hand tied bags. Sandalwood and black coconut oil was stacked in tiny bottles on folding tables. Red, green, and black Rasta caps hung on poles like Kwanzaa ornaments. All across the park Black artists twisted and hammered out bronze bracelets and decorated cowrie shells for the hundreds of brown and bare ankles moving across the grass. Curtis Mayfield and Bob Marley and Chaka were out playing each other on boom boxes situated north and west. The heart of my intimacy was all around me.

I turned and moved toward the dancing sisters in the middle of the park, a full circle of women pushing down the ground and pushing back the sky with their bangle and beaded arms. I was shy to dance this African dance that I didn’t think I "knew" but the sisters were so encouraging. I danced with the sisters and the children in the middle of the park. Suddenly, out of nowhere, another sister came towards me with her arms open. I couldn’t believe my Black girl eyes. "Andrea?" So many years had passed since we had seen each other and she was wearing Afro-centric clothes just like me, with thick lion size dreadlocks like ropes of sunflowers on her head, just like me. We recognized our similar transformations. She took both my hands inside her own and we embraced and danced with all the rest in the middle of the sun-drenched day. Somewhere along the path of our different lives we had both released the safe and predictable clothes and looks of our family-people and stepped fully into our own spirits and selves. Andrea danced over to her two children, scooped them up softly and introduced me to them. One boy and one girl with their own African names and smiles as big and sweet as cherry pie. Andrea was now Noni. Lynn was now Nikky. We had both been transforming ourselves into a new age Black woman determined to live in the world on our own new Black womanish terms. I held the children close whispering their names to myself. Their black coconut scented skin glistened in my arms. Noni wanted to know if I had children of my own at home. I remember telling her, "Not yet."

At the end of the day we exchanged addresses and before the week had passed Noni and the children arrived at my tiny apartment and sat with me at my converted poetry-writing table. Together we destroyed pots of tofu, greens, and brown rice. Laughter and the sound of free children bounced off every wall. We caught up with each others lives, sort of, and found ourselves staring at each other from time to time, marveling at how we had escaped law school, medical school, or some other professional finishing school, and how joyous we were to be on the path of being the Black women we had dreamed of becoming.

Noni and Nikky. These were our new names, names we had embraced along the way, names that felt more kindred to our spirits. We talked about our beautiful parents and what our blood brothers and sisters were doing with their lives. We talked about the state of the race. We talked about giving up the fried chicken and barbecue of our youth and loving Black people and Black culture more than corn candy on Halloween. I was mighty glad to be back in her beautiful sight and she in mine. It was one thing to meet new people along the way of life but being able to reconnect with someone who had been there at the beginning was a precious private thing. We didn’t talk about love or our relationships. In hindsight, perhaps we were both saving the tougher, harder to speak on topics for the next visit.

Noni had studied dance with Arthur Hall in Philadelphia and become a culture keeper. In the days ahead of that reconnection lunch she would leave Atlanta and found a children’s theatre and African culture center in Charlotte. I was just a journeying baby poet steadily gathering up alphabets in every jacket pocket that I owned. I soon fell in love and moved out to the West Coast in 1985. I thought I would settle there but after my first book of poetry came out I was offered my first teaching job at the University of Kentucky in 1990. Noni and I saw each other only a few more times over the next few years.

In September of 1990, Mama Finney called. I could hear her voice breaking into a waterfall of silver slivers. "Baby, Bunnie’s dead." I thought I misheard her so I changed the phone to the other ear and said, "Mama, stop playing." My heart had already begun to seize up. My mother never played about death and I only knew one Bunnie. Andrea could not be dead at 33?

As the story unfolded, the story blew every one of us down into the feet and arms of the ground. Noni had been home in Charlotte, N.C. when her estranged husband arrived at the house. The children were playing in the yard. 27 minutes later Noni was dead, stabbed with the kitchen knife. Minutes later her estranged husband hanged himself in the basement before the police arrived.

I drove from Lexington to Atlanta to see her for the last time. I do not remember actually driving. I remember pulling over at rest stops to weep and beat the steering wheel with my open fists. As I held on to the wheel, as I got back on the highway, there was Noni, alive and well in front of me. Smiling. There was Noni lifting, flying, dancing, her beautiful self, everywhere I looked. There was Noni on the back trunk of the car in front of me with her dangling ankh earrings and clicking tongue, calling her Black people deep into the life circle. There was Noni again rising above the pines on the side of the road, her amber Noni-light silhouette filling the day sky brighter. There was Noni with her arms out and open, like some extra set of Black woman wings, with her legs akimboed and pursed just so, like sweet black lips, her body aimed up and higher than any human body I had ever seen dance before. It had been such a thing of beauty to watch Noni dance and to witness a kind of physical and spiritual perfection. Noni had come to earth to dance and dance she did, every move she made refusing defeat or retreat or invisibility. When Noni Olaniyan danced you saw the human physics of flutter & hum, a new feminine language for living in and above this crazy world.

I arrived at the church early. I was the 2nd car in the parking lot. I sat in the car awhile and prayed to the ancestors to give me the strength that I knew I would need to make it through her Homegoing ceremony. It was a typical September Georgia day. All corners of the earth as far as I could see were bright with fall light and shadow. As I walked into the church I could see the casket open there at the front. I walked up to her whispering her name. As I moved closer I lay both hands on her right arm, which was the closest part of her to me, whispering something that I don’t quite remember. In her casket she was Nefertiti, or maybe was she Hatshepsut, in repose, draped in gold kente with a silver African scepter in her left hand. I had brought five cowries for her journey beyond the earth. I emptied them out of the honey jar and placed two inside the cloth near her right arm.

The sisters she had danced with in Atlanta and Charlotte danced with her one last time. The brothers who had drummed for her, drummed for her one last time. I remember the sound of her father who could not stop crying and how his sobbing filled the church. I remember the sight of her beautiful mother who never took off her dark glasses. I can still see her brother trying his best to hold up their father and their unbearable grief. Members of the family were holding the four babies. The preacher called Noni "beautiful and driven." I don’t know how she did it but Noni’s sister sang, "You take my breath away." The woman sitting next to me, whom I did not know, held me, and let me weep the first, second, and third layers of my hurt away. The frankincense burned through us and held us close to each other in an old translucence. I got in line to greet the family, lingering the longest with Noni’s mother, who caught my hand in that way a Black women who knows you and knows your people, catches your hand, she said, "Darling, we have to take care of our girls. Our children are not supposed to die first."

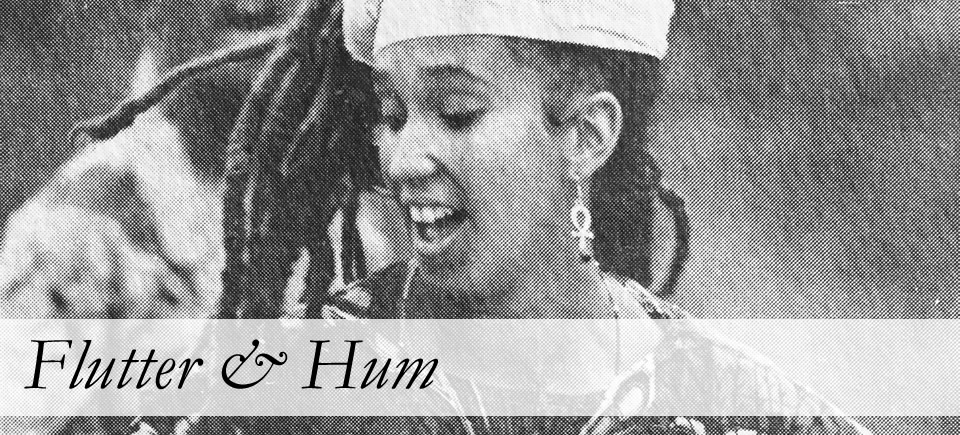

This is my favorite photograph of Noni. It was taken in the Charlotte, North Carolina, at one of those African arts festivals, the kind where you could always find Noni gathering the children into a circle of light and life. Every inch of her soul was focused on teaching the next generation their value, worth, and glory. This was a woman devoted to moving and singing and rejoicing in the beauty of who our children were and who they could be.

Twenty-six years have passed since Noni flew on beyond the treetops. I still close my eyes when I need to hear Noni’s long arm of silver bangles moving like a sweet shimmering shower of light. I still see the fire and sun circling her beautiful face as she moves to the music of the drums or to some other music only Noni girl could hear. I still feel her locks brushing up against my own as we embrace and she takes my hands inside hers just to say, "Sister, sister, come on now, tell me how you really doing?" Noni Olaniyan was all Black woman electricity and she walked the face of this earth for a short while with the widest deepest open arms. She loved her African cloth, her head wraps, her dreadlocks, her tofu, her juices, her incense, her cowrie shells, her culture, her drums, her beautiful joyous children, and all things good and ancient and African and true. I send this memory of her out into the world to you today, as a selfish blessing, just so you might miss her too.

—Nikky

Photograph by: Bob Leverone for The Charlotte Observer